Halley’s Comet is Edmond Halley’s namesake. Happy birthday, Edmond!

The scientist behind Halley’s Comet

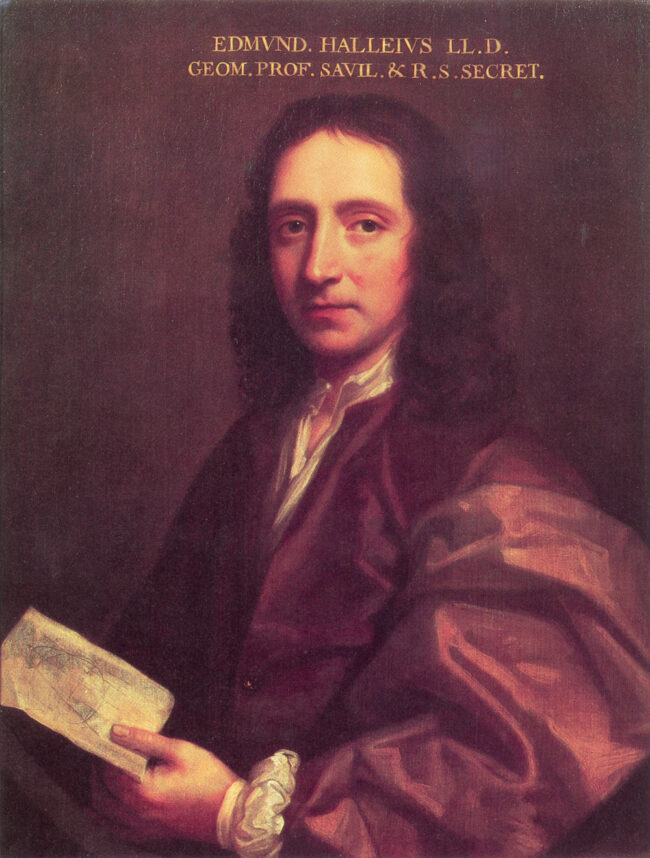

November 8, 1656, is the birthdate of English astronomer and mathematician Edmond Halley. Born near London, he grew to become the first to make the leap of the imagination required to understand that comets orbit our sun. And he was the first to calculate the orbit of a comet, now one of the most famous of all comets, named Comet Halley in his honor.

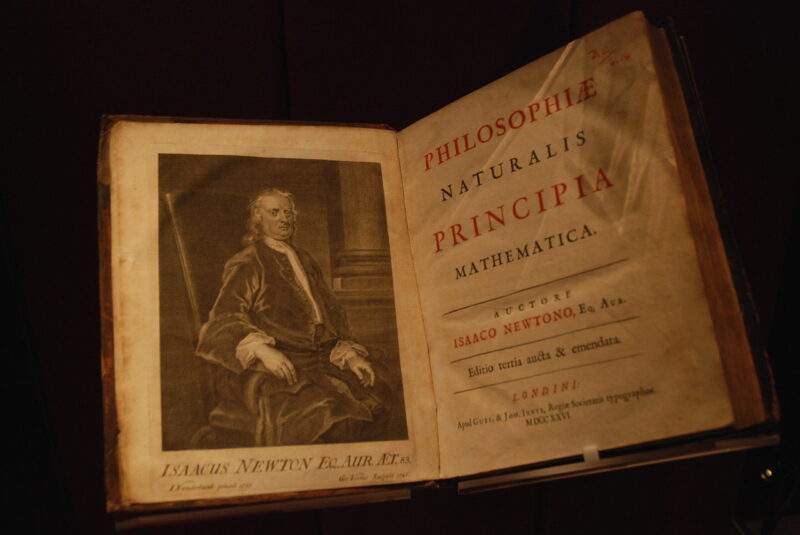

Halley was also friends with Isaac Newton and contributed to Newton’s development of the theory of gravity, which helped establish our modern era of science, in part by removing all doubt that we live on a planet orbiting around the sun.

When Halley’s Comet last appeared in Earth’s skies in 1986, an international fleet of spacecraft were there to meet it. This famous comet will return again in 2061 on its 76-year journey around the sun. It’s famous partly because it tends to be a bright comet in Earth’s skies. And the length of its orbit – approximately 76 years – isn’t so different from that of a human lifespan. So, most people can see Comet Halley once in a lifetime, while some lucky people might be able to see it twice.

But it’s also famous for another reason. In Edmond Halley’s time, people didn’t know that comets were like planets, bound in orbit by the sun. They didn’t know that some comets, like Halley’s Comet, return over and over.

The 2024 lunar calendars are here! Best Christmas gifts in the universe! Check ’em out here.

Halley’s prediction

In 1704, Halley became a professor of geometry at Oxford University. The following year, he published A Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets. The book contains the parabolic orbits of 24 comets that graced Earth’s skies from 1337 to 1698.

It was in this book that Halley made his magnificent prediction.

The return of Halley’s Comet

In his book, Halley remarked on three comets that appeared in 1531, 1607 and 1682. He used Isaac Newton’s theories of gravitation and planetary motions to compute the orbits of these comets. He found remarkable similarities in their orbits. Then Halley made what was, at that time, a stunning prediction. He said these three comets must in fact be a single comet, which returns periodically every 76 years.

He then predicted the comet would return, saying:

Hence I dare venture to foretell, that it will return again in the year 1758.

Halley didn’t live to see his prediction verified. It was 16 years after his death that – right on schedule, in 1758 – the comet did return, amazing the scientific world and the public.

It was the first comet ever predicted to return. Thus, we now call it Halley’s Comet, in honor of Edmond Halley.

Halley, Flamsteed and a Mercury transit

The 17th century was an exciting time to be a scientist in England. The scientific revolution gave birth to the Royal Society of London when Halley was only a child. Members of the Royal Society – physicians and natural philosophers who were some of the earliest adopters of the scientific method – met weekly. The first Astronomer Royal was John Flamsteed, remembered in part for the creation of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, which still exists today.

After entering Queen’s College in Oxford as a student in 1673, Halley met Flamsteed. Halley had the chance to visit him in his observatory on a few occasions, during which Flamsteed encouraged him to pursue astronomy.

At that time, Flamsteed’s project was to assemble an accurate catalog of the northern stars with his telescope. Halley thought he would do the same, but with stars of the Southern Hemisphere.

Halley’s Southern Hemisphere expedition

His journey southward began in November 1676, even before he obtained his university degree. He sailed aboard a ship from the East India Company to the island of St. Helena, still one of the most remote islands in the world and the southernmost territory occupied by the British. His father and King Charles II financed the trip.

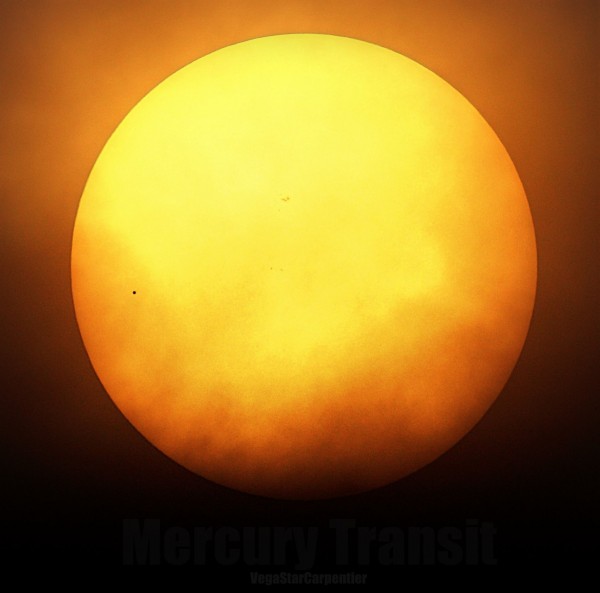

Bad weather made Halley’s work difficult. But, despite this, when he turned to sail back home in January 1678, he brought records of the longitude and latitude of 341 stars and many other observations. One of these observations was a transit of Mercury, about which he wrote:

This sight … is by far the noblest astronomy affords.

Cracking the code of planetary motion

Halley published his catalog of southern stars by the end of 1678. And – as the first work of its genre – it was a huge success. No one had ever attempted to determine the locations of southern stars with a telescope before. The catalog was Halley’s glorious debut as an astronomer. In the same year, he received his M.A. from the University of Oxford and was elected a fellow of the Royal Society.

Halley visited Isaac Newton in Cambridge for the first time in 1684. A group of Royal Society members, including physicist and biologist Robert Hooke, architect Christopher Wren and Isaac Newton, were trying to crack the code of planetary motion. Halley was the youngest to join the trio in their mission to use mathematics to describe how – and why – the planets move around the sun. They were all competing against one another to find the solution first, which was very motivating. Their problem was to find a mechanical model that would keep the planet orbiting around the sun without it escaping the orbit or falling into the star.

Hooke and Halley determined that the solution to this problem would be a force that keeps a planet in orbit around a star and must decrease as the inverse square of its distance from the star. Today we know this as the inverse-square law.

Hooke and Halley were on the right track, but they were not able to create a theoretical orbit that would match observations, despite Wren donating a monetary prize.

Newton solves it

Halley explained the concept to Newton, also explaining that he couldn’t prove it. Newton, encouraged by Halley, developed Halley’s work into one of the most famous scientific works to this day, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, often referred to simply as Newton’s Principia.

Halley became Astronomer Royal

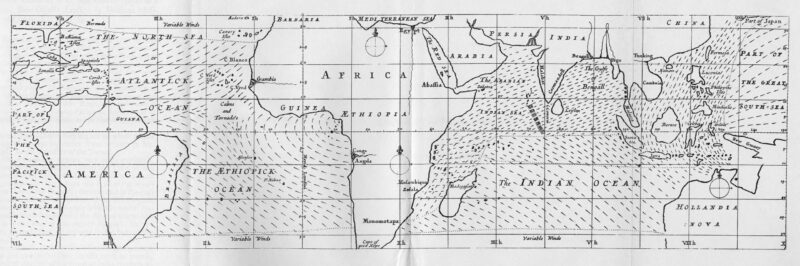

Halley is also known for his work in meteorology. He put his talent of giving meaning to great amounts of data to use by creating a map of the world in 1686.

The map showed the most important winds above the oceans and is the first meteorological chart ever published.

Halley kept traveling and working on many other projects, such as attempting to link mortality and age in a population. This data became important for actuaries calculating life insurance.

In 1720, Halley succeeded Flamsteed and became the second Astronomer Royal at Greenwich.

Bottom line: Astronomer Edmond Halley is famous for predicting the return of the comet that we now know as Halley’s Comet. Edmond was born on November 8, 1656.